40 years since the successful salvage of King Henry VIII’s Mary Rose, achieved with help from the Offshore Oil and Gas Industry ‘Giants’

Published on 11 October 2022

This year marks the 40th anniversary since the raising of King Henry VIII’s favourite warship the Mary Rose, on the 11th October 1982, watched via a BBC live broadcast over two days by 60 million people worldwide and with HRH Prince Charles in attendance on both days.

In January 1982, the archaeological excavation of the contents of the Mary Rose was taken to the next level when the decision was taken to raise the hull of the Mary Rose and bring her home to Portsmouth, UK where the ship was built in 1510. The Mary Rose sank not far from Portsmouth in the waters of the Solent on the 19th July 1545.

IMCA Contact

Kester Keighley

Technical Assistant – Diving

Contact

To help achieve this, the Mary Rose Trust turned to the North Sea Offshore Oil and Gas industry and received support from many companies. These included Comex Houlder (now part of Subsea 7), who loaned the surface demand diving equipment and a decompression chamber and Howard Doris who loaned their 1,000 tonne crane barge Tog Mor (now owned by Allseas). The total lift of the delicate hull remains was 540 tonnes, which included the weight of an underwater lifting frame (ULF) and a cradle, both built by Babcocks. At the time, Tog Mor was being mobilised nearby in the Solent prior to heading out to West Africa to carry out a long-term project for Shell. Sonardyne had been involved since 1975 with survey and position fixing

whilst BP and Shell were on board as supporters for many years.

Over the previous years, and with a final push from April to June 1982, the contents of the Mary Rose had been excavated in an archaeological manner leaving the most important artefact of all, the remains of the hull. The ship was at an angle of 60 degrees and only half of it had survived including most of the starboard side, a small part of the port side, a portion of the bow castle and most of the stern castle. During the excavation and salvage most of the internal structure such as deck planking (800 timbers in total) were dismantled and removed so the final lift was just the empty hull.

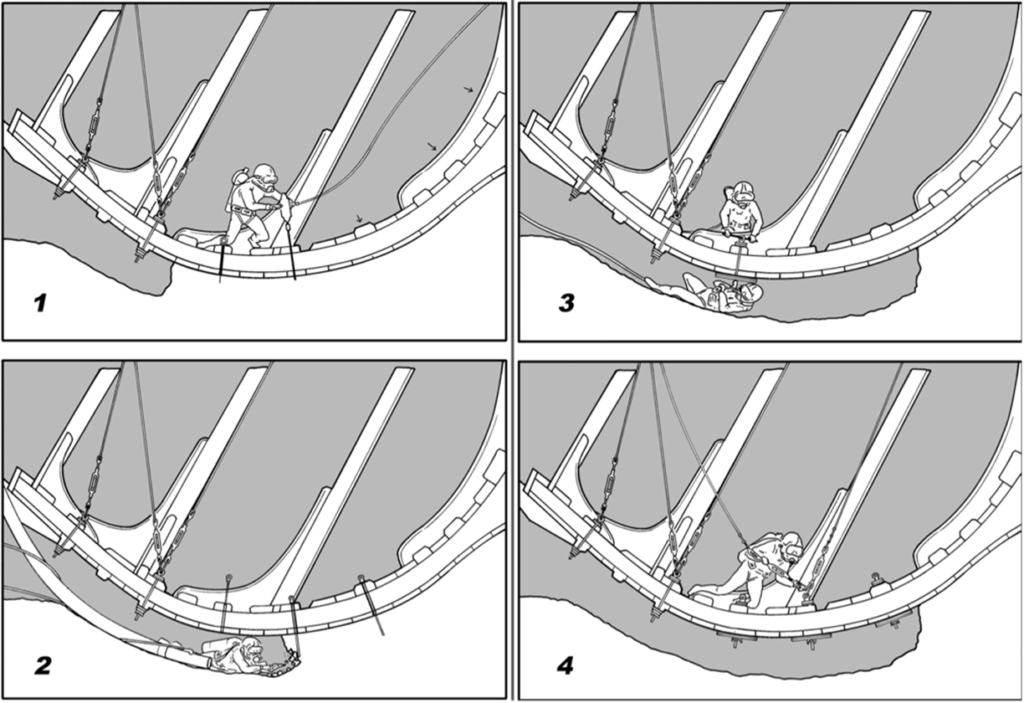

The salvage method finally adopted was to place a four-legged underwater lifting frame (ULF) over the hull (Figure 2.1) and then attach the hull to the lifting frame as shown in Figure 1. This was achieved by drilling 170 holes through key structural timbers at critical points (Figure 1.1), installing steel ring bolts and tunnelling under the hull (Figure 1.2) and installing backing plate assemblies with securing nuts (Figure 1.3). Finally, a number of wires were installed between 67 of the critical points and the ULF above (Figure 1.4) creating a cat’s cradle for lifting the hull. Equal tensioning throughout the hull was achieved with a rigging screw (turnbuckle) on each wire. The remaining unwired bolts acted as clamps to firmly hold the hull together.

The diving to prepare the hull for lifting was carried out by two teams working together using surface supplied diving equipment: one recruited from the Mary Rose divers, who had been involved with the excavation since 1979 and trained up to full HSE standards, and the other from the Royal Engineers Diving Establishment (REDE), Marchwood, beside Southampton Water. The depth to the seabed was 12 metres but inside the hull was deeper and tunnelling under the hull took us to a maximum depth of 20 metres. Most of the salvage diving, because of the depth and longer dives, required decompression, mainly surface decompression.

The Mary Rose divers carried out the remaining archaeological work and the delicate work on the hull like drilling holes through the hull structure, installing bolts with backing plates and wires from key bolts to the ULF. The Royal Engineer team undertook some of the heavy engineering aspects of the salvage including digging some of the holes for the ULF legs, bringing out and lowering the ULF over the site and operating the underwater end of the hydraulic jacks. Both teams carried out the tunnelling under the hull to secure the bolts through the hull.

The lift was divided into a number of controlled stages, monitored by tell-tales placed on the hull at specific places to ensure that no part of the hull bore excessive stresses. The first stage was to hydraulically jack the ULF up its legs with the Mary Rose hanging beneath (Figure 2.1). This measure of control was absolutely vital to overcome the enormous suction caused by the seabed mud and soft silts. This was monitored by Mary Rose divers checking that the hull was being raised evenly off the seabed centimetre by centimetre.

The next stage (Figure 2.2 and 2.3) was the underwater lift and transfer of the hull, hanging below the ULF, from its original position in the seabed into a cradle placed on the seabed nearby. This was the first operation using Tog Mor and the transfer was guided using Sonardyne Compatts (Computing & Telemetering Transponders) to monitor the position of the ULF and hull during its transfer to the cradle. The final docking was achieved using divers positioned on the cradle to guide the legs into position, as only three of the four legs could be docked because the north-east leg was accidently bent during the transfer, having caught on the seabed. Eventually the offending leg was cut off underwater by the Royal Engineer divers and the corner of the ULF was then suspended using an extra fly-hook from Tog Mor.

The next stage (Figure 2.3) was the final lift to surface of the cradle, complete with ULF and hull, and landing this package onto a barge for the final journey bringing the Mary Rose home to Portsmouth. Anyone who watched documentaries or newsclips about the salvage will be aware that during the final lift out of the water there was an unforgettable, heart-stopping crunch when the south-east corner of the ULF slipped down to the level of the hull. A tubular pin used to restrain the leg had given way, and the sheath or collar which connected the ULF to the leg had slipped by more than a metre. Fortunately, no damage was done to the hull. The lift continued and by teatime on Monday 11th October the whole package was safely landed on the barge and Tog Mor’s crane hook could be disconnected.

Once back in Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, the ULF was removed and the cradle and hull were wheeled across onto a smaller barge which was then floated into Dry Dock Number 3 after 437 years underwater. This Dry Dock (a Grade 1 Scheduled Ancient Monument) is near to where the Mary Rose was built and is next door to Nelson’s flagship, HMS Victory. In 1983 a temporary building was constructed over the ship and in 1984 a museum displaying the artefacts was opened in a building nearby. In 1985 the cradle and hull were turned upright and many of the 800 timbers that had been removed underwater were reinstated. The hull at last began to look like a ship. A new building was built more recently over and around the Mary Rose which not only houses the ship but also displays many of the artefacts. This new world-class museum was opened in May 2013 revealing a rich legacy and our best insight into life in Tudor times.

Last summer, the Mary Rose Trust introduced a new visitor experience relating to the sinking of the Mary Rose – ‘Experience 1545 – When Their World Ended’ introduced by Dame Judi Dench. Later this year, to mark 40 years since raising the Mary Rose, a 4D multi-sensory cinema will immerse guests in a journey through the search, discovery, excavation and recovery of the Mary Rose.

The Mary Rose – flagship of Henry VIII | The Mary Rose

Author: Kester Keighley, archaeological diver 1981-1982 and member of the Mary Rose salvage team.